Picasso Quote There Is No Past or Future in Art

Visual art tells yous what era it comes from. During different historical periods, certain styles, motifs, and colour palettes, boss—and then even if experts don't know the creative person and origin of a piece, they can often pin it to a particular moment in time. In today's consequence, we focus on two very unlike schools of art that flourished in the early 20th century. An Atlantic video producer shows us how she created a 1930s-inspired animation, and Karen Yuan reports on how Picasso influenced the creative mural when his work outset arrived in the United states. Finally, nosotros'll get out you with a question: There are certain characteristics that allow the states to engagement the art of the by, but will nosotros continue to be able to engagement the fine art of the time to come?

—Caroline Kitchener

How to Animate Similar It's 1932

Atlantic animator Caitlin Cadieux explains her process for creating '30s-inspired art.

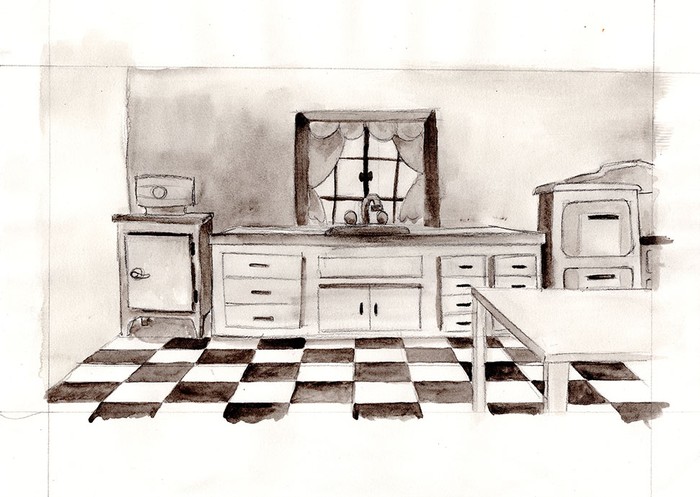

As part of our Atlantic Archives project, I animated an essay past Helen Keller: "Put Your Hubby in the Kitchen," published in The Atlantic in Baronial, 1932. Keller'due south story was a stern rebuke of the (predominantly male) "captains of industry" of her day, blaming them for wasteful business practices. Keller posits a businessman named Mr. Jones, drawn from overwork and overproduction, who agrees to swap places with his homemaker married woman. She argues that men would learn far better concern sense by taking on the household management tasks that traditionally fell to women.

I wanted to adapt the slice in the mode of cartoons from that fourth dimension menstruation, which presented some unique challenges. Animations in the 1930s were painstakingly created by mitt using traditional materials, rather than the digital tools we use today. They also included some problematic representations of gender. You lot can sentry the video to see where I ended upwardly. Here'due south what I learned in getting at that place.

- Exercise your (history) homework

The tone and vocalization of Keller's essay struck me as very similar to a public service announcement–way video from the aforementioned period. For reference, I watched several PSAs, such as this advertizement past the federal government promoting the New Deal, and this safety alert almost the dangers of gasoline in clothes laundering. The fact that these PSAs were invariably narrated by men allowed us to prepare upwards a contrast with Keller'due south feminist viewpoint. (The Atlantic's ain Alex Wagner provided the voiceover for u.s.a.. Married to sometime White Business firm chef, Sam Kass, Alex was a particularly fitting reader for "Put Your Husband in the Kitchen"!)

Considering Atlantic Athenaeum is an blithe historical series, it made sense to draw on the visual sensibilities of this essay's era, the 1930s. In 1928, with the introduction of sound cartoons and Walt Disney'south rising to prominence, blitheness entered a Golden Historic period. Cartoons at the time ofttimes featured slapstick comedy and surreal adventures with little or no dialogue. Walt Disney's Silly Symphonies blithe series, which began in 1929 and ran through 1939, is a perfect exemplar of the genre. Silly Symphonies featured grayscale, hand-fatigued blitheness over paw-painted, watercolor backgrounds, similar to what I chose for the piece. I was also inspired by the innocent humour of Disney's early on Mickey Mouse shorts.

-

Try to avert '30s-era sexism

I designed Mr. and Mrs. Jones in a style that roughly emulated Fleischer Studios' flapper girl, Betty Boop. Key details of that style include round shapes and "prophylactic hose" limbs, loose, bendable arms and legs that made the characters easier to depict. Cartoons produced in the 1930s were thoroughly steeped in the sexist mores of the fourth dimension. The merely prominent female animated character of the period, Boop was considered developed amusement, often depicted pulling down her short, cerise apparel, and frequently subjected to male ogling. By animative Mrs. Jones—the potent, confident female grapheme driving Keller's story—in the same style, I could take the sexist narrative that has long surrounded Boop, and turn information technology on its head.

-

Create a storyboard

"Storyboarding" means illustrating every piece of a script sequentially, creating a visual reference that guides an animator through a video from beginning to end. This technique, invented by Disney animators in the '20s and early on '30s, is a key step in making almost all of today'southward animated work. Below, yous can see how I illustrate each line of the script to show what will be animated. After completing a storyboard, I pause it up into segments chosen 'shots' or 'scenes.' In total, my Helen Keller video has 32 distinct scenes. You can view the full storyboard here.

/media/img/posts/2018/03/Storyboard/original.png)

-

Animate with traditional cel animation

With the storyboard in place, I could start to animate. Nearly studio animation done present is blithe in 3D, which doesn't use drawings at all. But in keeping with the style of the time, I wanted to use traditional cel blitheness, which is extremely fourth dimension- and labor-intensive: Information technology requires making around 12 unique drawings per second of animation.

Traditionally, artists began with pencil and paper. Each cartoon was and so traced with ink onto a transparent sheet chosen a cel, and color was painted on manually. Adhering to this exact process would have meant bravado our borderline, so I cheated a little and used a digital paint plan. This as well immune for instant playback; in the '30s, animators could only review their work after it had been photographed, one picture at a time. You lot can see my blitheness procedure, step by step, here.

Below is an example of a walk cycle. Characters are amid the most difficult aspects of a scene to animate, due to the complexity of human move. Considering I added this sequence late in the process, I had to breathing the walk backwards from Mr. Jones' terminal continuing position. The second image shows how I inked and colored the drawings for the walk cycle digitally.

/media/img/posts/2018/03/03_Inked_Frames/original.png)

I also needed to brand the artwork for the backgrounds of each shot. I painted each background with black gouache, an opaque watercolor, to highlight the details and echo the watercolor backgrounds of 1930s cartoons. While today'south animation, produced digitally in 3D or 2D, is still beautiful, there is a unique richness to watercolor paintings done past hand.

Equally an animator, I learned a groovy deal virtually my craft from this project. Studying the precursors of our current digital techniques has given me a greater agreement of the process every bit a whole. Turnarounds are tight and blitheness is still labor-intensive, but today nosotros are lucky to exist able to produce professional person-quality animation relatively fast. Past practicing the techniques of the 1930s, I recollect I've actually sped upwardly my workflow!

—Caitlin Cadieux

Can an Artist Still Shape an Era?

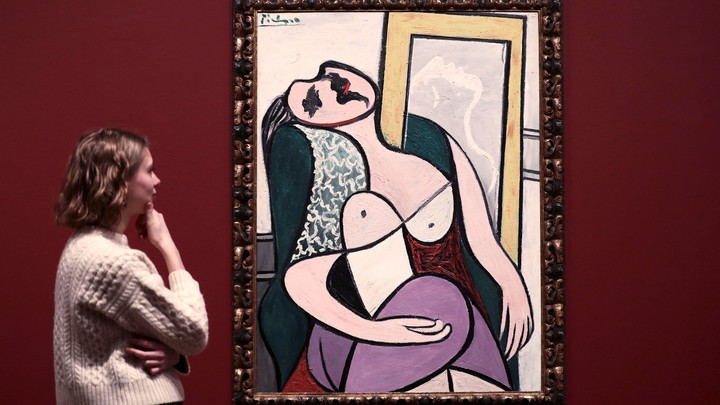

Karen Yuan discusses why it may be hard for another creative person to have an bear on as great as Picasso's.

When Pablo Picasso died in 1973, the painter Willem de Kooning said, "Certain artists are always with me, and surely Picasso is ane of them." Since his beginning exhibition in America more than a century ago, Picasso has shaped the imagination of American artists.

That first showroom, at the photographer Alfred Stieglitz' New York gallery in 1911, shocked Americans with Picasso's intensely abstract Cubist works, which used geometric shapes to represent various perspectives at one time. Information technology was a new vision in fine art for a new time—avant-garde fine art was rising to prominence aslope skyscrapers and jazz. The almost innovative artists in America at the fourth dimension began painting Cubist works, including Marsden Hartley, one of the pioneers of modernist American art.

/media/img/posts/2018/03/Screen_Shot_2018_03_21_at_2.26.29_PM/original.png)

After his second major exhibition in America, a twoscore-year retrospective of his piece of work at the Museum of Modernistic Fine art, which took place in 1939, Picasso'south affect on the fine art world broadened amongst artists. Well-known by and then, Picasso startled them again with new works, including Guernica, which responded to the Castilian Civil War. At the same fourth dimension, Earth State of war Two was just beginning. "The sheer violence and energy of his work … Artists felt that it really continued to what was happening in the world at that moment," said Michael FitzGerald, a Picasso scholar who curated the Whitney Museum's 2006 exhibition on the artist's influence on American art.

The exhibition was vast compared to previous ones. The sculptor and painter Louise Bourgeois wrote in her diary:

There was an exhibition of 400 paintings by Picasso here (40 years' piece of work). It was then beautiful, and it revealed such genius and such a collection of treasures that I did not pick up a paintbrush for a month. Complete shutdown. I cleaned brushes, palettes, etc. and tidied everything … Once the source of joy disappeared, life became depressing.

Jackson Pollock covered upward Picasso-inspired shapes with his drip paintings. A review of the Whitney exhibition in New York magazine said that, for artists, "[Picasso's art] embodied freedom, change, and possibility." The modernist painter Stuart Davis, reaching back to Cubism, added a twist of jazz to it.

Picasso'south influence echoed in American art throughout the second half of the 20th century. The typography in some of his Cubist work, and Guernica, with its newspapery, cartoon-similar await, influenced Pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. In the 1980s, the chaos in the artist Jean Michel Basquiat's paintings reflected the subsequently work of Picasso—Basquiat fifty-fifty defended a few paintings to him. Today, said FitzGerald, "the creative person who'due south had the greatest response to Picasso's work is George Condo," who created the surreal posters for Kanye Westward's album My Cute Dark Twisted Fantasy.

FitzGerald contends that few other artists have had the same pervasive bear upon on American art every bit Picasso. Every bit for artists in the futurity—"it's hard to imagine," he admitted, given the fragmentation of the contemporary art earth. In the 20th century, art had a geographic center, such as Paris or New York. Today, art has become globalized, with more artists and more than ideas in more than places. "Information technology's much harder to have a comprehensive sense of what artists are interested in," FitzGerald said. A style similar Cubism may not have the same monolithic event that it had in the past.

That fragmentation has been occurring since the 1970s—the same decade Picasso died. After that, said FitzGerald, "the sense of cohesiveness of argument really shattered, and it'due south never been put back together again, and I don't think it ever will exist." The absence of a new champion in the art world may chemical compound Picasso's indelible effect on it.

In 1923, Picasso wrote a statement to his friend Marius de Zayas, who helped organize that first exhibition at Stieglitz' gallery, on art's relationship with fourth dimension. While he felt there existed periods of art more than "complete" than others, he didn't believe in a by or future for fine art. "If a work of art cannot alive always in the present, it must not be considered at all," he said. "All I have always made was made for the nowadays and with the hope that it will always remain in the nowadays."

—Karen Yuan

Will Today's Art Eventually Expect "And then 2018?"

We asked CityLab staff author Kriston Capps to reverberate on how today's art will be seen past fine art enthusiasts of the future.

There'due south a lens effect in art: The more than recently it was created, the harder it is to place. Art from the past falls into corking categories like Baroque or De Stijl, while contemporary art makes for difficult sorting. Even the occasionally stable tentpoles for art of the 21st century, whether information technology'south mail-black or social exercise or zombie formalism, are built on the shifting sands of constant art-earth bickering.

But the fact of the matter is that art from the past is subject to greater revisionist force per unit area than the local museum may testify. Especially at present, as women artists and artists of colour—or artists working exterior the W—are finding buy in collections, exhibits, and scholarship, the canon is shifting. Meanwhile, fine art of the moment is usually quite piece of cake to situate once the moment has passed. Think of art in the terms that employ to music and it might make more sense: Eventually, the bleeding-edge sound of alternative metal joined the ranks of archetype stone, then disappeared from the radio altogether in favor of pop music, which is today generally the hip-hop sub-genre known as trap. Tomorrow information technology volition sound like something else.

Contemporary fine art'southward no dissimilar: While it might seem like anything goes at art festivals today, give it enough time and art, as well, will look distinctly '90s (Julian Schnabel), '00s (Julie Mehretu), and '10s (?).

—Kriston Capps

Today'southward Wrap Upward

-

Question of the Day: Volition the art of today exist as easy to date as the art of the past?

-

What'south Coming: This week marks the 15th anniversary of the Republic of iraq State of war. On Friday, nosotros'll reflect on lessons learned since the start of the conflict.

-

Your Feedback: How are nosotros doing? Have our survey below.

/media/img/posts/2018/03/imageedit_2_3181866120/original.png)

We want to hear what you lot think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

Karen Yuan is a quondam assistant editor at The Atlantic.

/media/None/Caitlin_Cadieux_grey/original.png)

Caitlin Cadieux is a former animator at The Atlantic.

Kriston Capps is a staff writer for CityLab covering housing, architecture, and politics. He previously worked as a senior editor for Architect magazine.

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/membership/archive/2018/03/how-art-reflects-the-age-it-comes-from/556103/

0 Response to "Picasso Quote There Is No Past or Future in Art"

Post a Comment